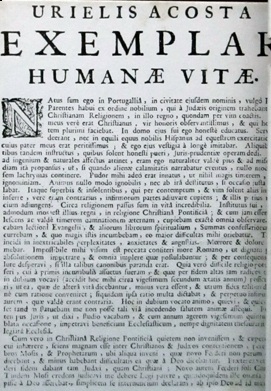

This was written by your editor after reading the autobiography of Uriel daCosta.

I thank you for pausing to allow me to tell you my story. My name is Uriel da Costa and this is my confession. I vow to speak the truth only. Neither embellish with pretties nor hide the ugliness of my life. You can judge if my actions where appropriate to my situation and to my convictions – or did I give in to easy to the social pressures of my community. To make others conform to their own religious practices has ever been the aim of those who practice them. It justifies their belief and calms their own doubts. If the doubter remains quiet and does not stir the dark waters of devotion they will gladly allow his presence and look the other way. But if he feels he is drowning in the sea of deceit and struggles to survive they will happily push his head under.

The city of Porto in Portugal was the place of my birth. It was in the year 1585 but I was not called Uriel then. The name given to me was Gabriel. I caused it to be changed when I changed my religion.

My father, Bento da Costa, of blessed memory, was a devoted Catholic. Our family was a respected part of Porto society for many years. The da Costas were merchants of some renown. My five brothers and I were well tutored. We lived in a large home in the best part of the city with servants always at our command. I was aware that my mother, Branca, was anciently descended from Jews who had converted to Catholicism. Although she dutifully followed my father to church every Sunday she tried secretly to observe Jewish customs when she could. When my father was away on business she would dismiss the servants and, with a cloth over her head, she would whisper words we could not understand while she wafted her hands over the candles on Friday nights. She seemed to be drawing in some spirit from the flames.

It was determined by my father that I should study church law and he sent me to the University of Cambria to that effect. When I returned I did, for a time, serve as church treasurer and, in fear of eternal damnation, I, every month, confessed my sins to our priest.

As part of my education I was encouraged to think deeply about church matters. And the more I thought about these things, the greater the troubles that arose in me. In the end, I fell into an inextricable state of perplexity, restlessness, and trouble. Sadness and pain devoured me. I found it impossible to confess my sins according to Roman rites in order to obtain valid absolution. I began to despair over my salvation. It was difficult to abandon a religion to which I had been accustomed ever since the cradle and which had established deep roots in me. I was around twenty-two years old at that time of doubt. I asked myself - Could what is said about life after death be a fiction? Does the faith given to such sayings agree with reason? My reason ceaselessly whispers things altogether contrary my faith.

I began to read the Torah and the prophets to see what Judaism had to offer. I became convinced that the Law of Moses was truly revealed by God and I decided to follow in the light of that Law. Living openly (or even secretly) as a Jew was denied permission in Portugal. The Inquisition of Spain had become active in our country. But then my father became ill and in a few days died. In the next months we converted much our wealth into jewels that could be carried secretly and in 1617 my mother and I and two of my five brothers embarked on a ship that carried us to Amsterdam. I had learned that a community of Jews from Spain had newly established themselves there and were living quite openly without fear as Jews.

My brothers and I were circumcised and we began to familiarize ourselves with Jewish life. My mother changed her name to Sarah and I to Uriel. Trouble soon began. I was seeking for the religion of the bible., a pure devotion to the Laws of Moses. What I found was a religion of meaningless and superficial rules fabricated by rabbis who loved power. There were inventions that were totally foreign to the Laws of Moses. My eyes revealed the Jews as a sect of Pharisees caring naught for the true way but content - no anxious - to follow rules of the rabbis and gain their approval.

We removed ourselves to Hamburg and in 1616 I published a book of ten theses attacking the validity of the Talmud and all Jewish oral law. I showed that the Talmud, the writing of mere rabbies and should not be followed, as the rabbies claimed, as closely as the bible. That it was an abomination to do so. It would make the word of man equal to that of God.

At that time rabbinical authority rested in the older Jewish community at Venice and they declared against my book. Our little family was banned by the Jews of Hamburg so we moved back to Amsterdam. There my ideas were attacked by a Dr. Da Silva who wrote that I was in error to deny the immortality of the soul. and an eternal life in the hereafter. I stood fast. I was not in error. I argued that the human soul could not survive the death of the body. A soul is engendered by one’s parents. It is not created by God and then placed in the body, It is just a part of the body. It is the vital spirit in the blood. Consequently our souls are mortal and perishable and there can be no afterlife. Once a man is dead nothing remains of him nor does he ever return to life The Torah supports me saying nothing about an afterlife – the body is dust and to dust it does return.

On May 15, 1623 the Amsterdam Jewish community placed the ban of excommunication against me and cursed me. They called me sick and ordered that no man, woman, parent or stranger speak with me, that no one enter my home or show me any favor. Out of respect for my brothers they were given eight days before they were to separate from me forever.

I was enraged. I vented my anger through my pen. I composed another book in which I demonstrated the just character of my cause and in which, basing my argument on the Law itself. I showed explicitly the vanity of the traditions and actions of the Amsterdam Jewish community. I showed, as well, the discrepancy between their practices and Mosaic Law.

When the book was published the rabbis gathered them up and had them burned. Only a single copy survived the fire. Hidden in my house it was found many years later. They arrested me. I suffered 10 days in prison and they fined me 1500 guilders. My mother paid the fine. They tried to make her forsake me but she refused to leave our house and me.

I learned later that the temple governors discussed what they should do if my mother continued to disregard the banishment they had placed against me. Her love of me had carried her into my excommunication. Those unholy leaders were concerned that when it came that she should die there would be a question of where she should be buried. The rule was that anyone who disobeyed their edicts and died was denied burial in the Jewish cemetery. They sent to Venice for advice. The chief rabbi of Venice wrote back that an honest Jewish woman could not be refused a honest Jewish burial. Praise a rational man.

Only my mother resided with me. The servants fled and my mother kept the house and cooked. She held my hand and honored me by using my version of the rituals for Friday night and holiday services.

Night and day I did nothing but read and think about the Law. I came to the conclusion that the Law did not come from Moses but is only a human invention. It contradicts the law of nature in many respects, and God, the author of the laws of nature, could not contradict himself.

But the everyday concerns of life pressed in on us. Our money was almost gone. We had no fuel for a fire. Our meals were cheese and bread. My dear mother shivered in the winter night. I decided to try to reconcile with the Jewish community. I wanted also to marry and to have children. There was a young woman who did not look away when I passed her in the street. To the governors I retracted my previous words and disowned my writings and started living as best I could accordingly to the community’s rules. As they say, I was aping the apes, not stirring the waters. The governors relented. One of my nephews was permitted to live with us. People no longer avoided us. I became engaged to be married.

Two years later two Christians came to my house to ask for advice on converting to Judaism. I was honest with them. I told them that they were about to put a yoke around their necks and extracted from them a promise to keep my advice close. They did not do so but went straight to the Council. My nephew confirmed the visit of the Christians and also that he observed me violating the kosher rules by not keeping separate the milk and meat dishes. A cousin heard of these things and repeated them to all who would hear ill of me. Said cousin held that I was fouling the family name and the name of Judaism. It all came quickly to the Council’s ears, as he had intended.

In 1633, ten years after my first excommunication, a new one was pronounced against me, even more severe. My marriage was forbidden. They offered me an opportunity to atone if I would submit to flagellation, but I refused. For seven years I held out, alone and poor. My mother was gone. Everyone turned their backs to me. There was no one to talk with or work with. I searched in rubbish for scraps of food. From sundown to dawn I sat in utter darkness. Finally I surrendered. I wrote to the Council that I would confess my sins. They agreed.

When I entered the synagogue; it was filled with men and women gathered for the show. The moment came to climb the wooden platform that, situated in the middle of synagogue, served for public reading and other functions. I read out in a clear voice the text of my confession, composed by them: that my deeds made me worthy to die a thousand times. I had violated the Sabbath, I had not kept the faith, and I had even gone so far as to dissuade others from becoming Jewish. For their satisfaction, 1 consented to obey the order they imposed on me and to fulfill obligations they presented to me. In the end, I promised not to fall back into such turpitude and crime.

I finished my reading, descended from the platform, the chief rabbi approached me and told me, in a low voice, to retire to a certain area of the synagogue: I went, and the keeper told me to undress. Naked down ~my waist, my head veiled, barefooted, I had my arms around a column. My guard approached and tied my hands around the column. Once these preparations were finished, the cantor approached, took a whip and inflicted thirty-nine lashes with leather thongs upon my bare back, as required by tradition. A psalm was sung during the flagellation.

When it was finished, I sat down on the ground, and another cantor approached and released me from all excommunication. I then put on my clothes and went to the threshold of the synagogue. There I laid myself out and all who came down to exit the synagogue passed over me, stepping with one foot over the lower parts of my body. Everyone, young and old, took part in this ceremony. I turned my head and was able to see their faces as they stepped upon me. All looked impassively straight ahead including my brothers. But as my cousin came forth, the root cause of my woe, he dared to look me in the eye and smiled an evil smile at me as he stepped on me. The only other person who looked at me was the 8 year-old boy of the Espinoza family. His big brown eyes were full on my face and then he carefully stepped over without touching me.

When the ceremony was over, with no one left, I got up and went home. The next two days I spent writing my autobiography.

-----

When the autobiography was finished Uriel hid a brace of pistols under his cloak and went looking for his cousin. He found him in the street, leveled a pistol at him and pulled the trigger. The pistol misfired and the cousin fled. Uriel put the other pistol to his head and shot himself. The ball entered his head but did not kill him. He lay in his bed for three excruciatingly painful days before he died. He was 55 years old.